You’ve spent time considering the experience of individuals impacted by the criminal justice system with mental health disorders. What is your personal and professional background relevant to this area of work?

On a professional level, my connection to this work is unique. My journey to the bench is out of the norm. I practiced medicine for 18 years before going to law school. First, I practiced with a cardiac and thoracic surgery team. Then I transitioned into family practice as a primary care provider (PCP). My medical background gives me an interesting perspective when working with individuals with mental health challenges. When somebody in the courtroom looks tired or behaves oddly, I try to find out what medications they are taking. Similarly, when looking at urine analysis test results, I have a better and deeper understanding than most judges because of my medical experience.

I haven’t shared my personal background with many people, but my dad had significant bipolar disorder and an alcohol use disorder. As a result, I went through childhood watching my dad self-destruct. I didn’t know what I was watching or experiencing as a child, but I knew it didn’t feel good. My dad would get into trouble and be away from the family. Then he would come back and be okay for a while. Eventually, though, he would self-destruct again.

I have wondered what might have happened had my dad had the opportunity to engage in treatment for his co-occurring disorders. Maybe things would have turned out differently for him. It certainly would have had a lesser impact on our family. The flip side of that is that the experience prepared me for what I do now.

As a judge, you see and hear the lived experience of individuals in crisis. How has this work transformed your perspective of what it is like for those involved in the criminal justice system?

Frankly, I’m clueless about what barriers somebody must overcome to get into the courtroom because after I park in my reserved parking spot, I walk through a special door to a special elevator up to my chambers and then out to the bench. In contrast, there are many barriers that folks have to surmount to get into the courtroom, let alone navigate the legal system in general.

They’ve got to find a place to park, and parking around our courthouse is horrible. It is also not cheap. Or they have to find a ride or take the bus. They may need to arrange childcare. Then, getting through the door, there are security and magnetometers. Individuals have to remove their belts and shoes. Once inside, mental barriers are associated with figuring out which courtroom you’re supposed to be in, which may change daily.

Even after finding the correct courtroom, individuals are faced with the room’s design and can be intimidated when they don’t know where to sit or how to act.

Mental health adds a whole other layer. It’s not uncommon to have individuals come in who are off their medications or have medications that need to be adjusted. That means the person across from me could be experiencing auditory hallucinations, for example, and not even hearing what I’m saying to them.

I learned of a professional conference where a presenter was speaking to a group of judges, and at one point, unrelated audio started playing from one of the speakers. The presenter kept talking as if nothing was happening. Eventually, the judges in the audience spoke up and said they couldn’t follow what was being said and that somebody needed to turn the audio off. It turned out it was a mini social experiment for the audience to understand and experience what it’s like to have auditory hallucinations and how difficult it is to focus or follow directions.

I think having an awareness of mental illness is essential for judges. We work with people who may be unmedicated or experiencing side effects from their medications. Individuals may be dealing with things mentally that they have no control over. Maybe the person is experiencing depression such that they can’t stay awake. Perhaps they are in a manic phase and cannot pay attention because they’re bouncing all over the place.

I think those are real issues in my court every day. Therefore, having a team that understands these issues is a priority for me. A well-trained and trauma-informed staff of prosecutors, public defenders, caseworkers, and probation officers will do a better job helping individuals navigate the system.

What have you done to expand your knowledge and understanding of what it is like to be on the other side of the judge’s bench?

So, this started as a lark. I’d been on the bench for maybe 2 months. And we were in a judge’s meeting, and one of my colleagues commented on how frustrated they were about people not showing up for court, which is a genuine frustration in many courts. However, the conversation devolved to the sentiment that there wasn’t a legitimate excuse for failing to appear or arriving late because we have public transportation. In the therapeutic courts, we have bus vouchers, so even money isn’t a barrier. At that moment, I made a flip comment, saying, “I’ll bet you that if I gave every one of us two bucks, and we were dropped off randomly around Spokane County, none of us could get here on time.” The other judges responded that I was too new to the position and that I would understand after some time on the bench.

That interaction percolated in the back of my mind, and I kept wondering what it would be like to navigate public transportation and other life challenges from point A to point B. Fast forward 6 years, and after court one day, my judicial assistant and I were chatting about a court participant that had been late to court because they missed the bus. When I commented again that neither of us would be able to get to court on time, and my judicial assistant said, “Why don’t you try it?”

That was earlier this last spring, so I mulled it over and thought, “What are the two most common things in our therapeutic court that people must navigate? Probably observed random urine analysis (UA) tests and not being able to drive.”

Initially, I thought I’d do it for a month, but a colleague of mine said, “You’re crazy, do it for a day!” And I said, “No, I’ve got to at least do it for a week.” I picked a week in July when I knew I would be at the court and when I wouldn’t be out of town. Unfortunately, it ended up being the hottest week of the year.

I had one of the probation officers set up testing for me. I was given a card with a personal identification number, or PIN, on it, and I had to call every morning and listen to the message, and then it would tell me, based on my PIN, whether I had to test that day or not. I realized this wasn’t much forewarning, and I decided I needed to stash changes of clothes at the office, so I could walk around in the heat as much as necessary but still look presentable when I got back to work.

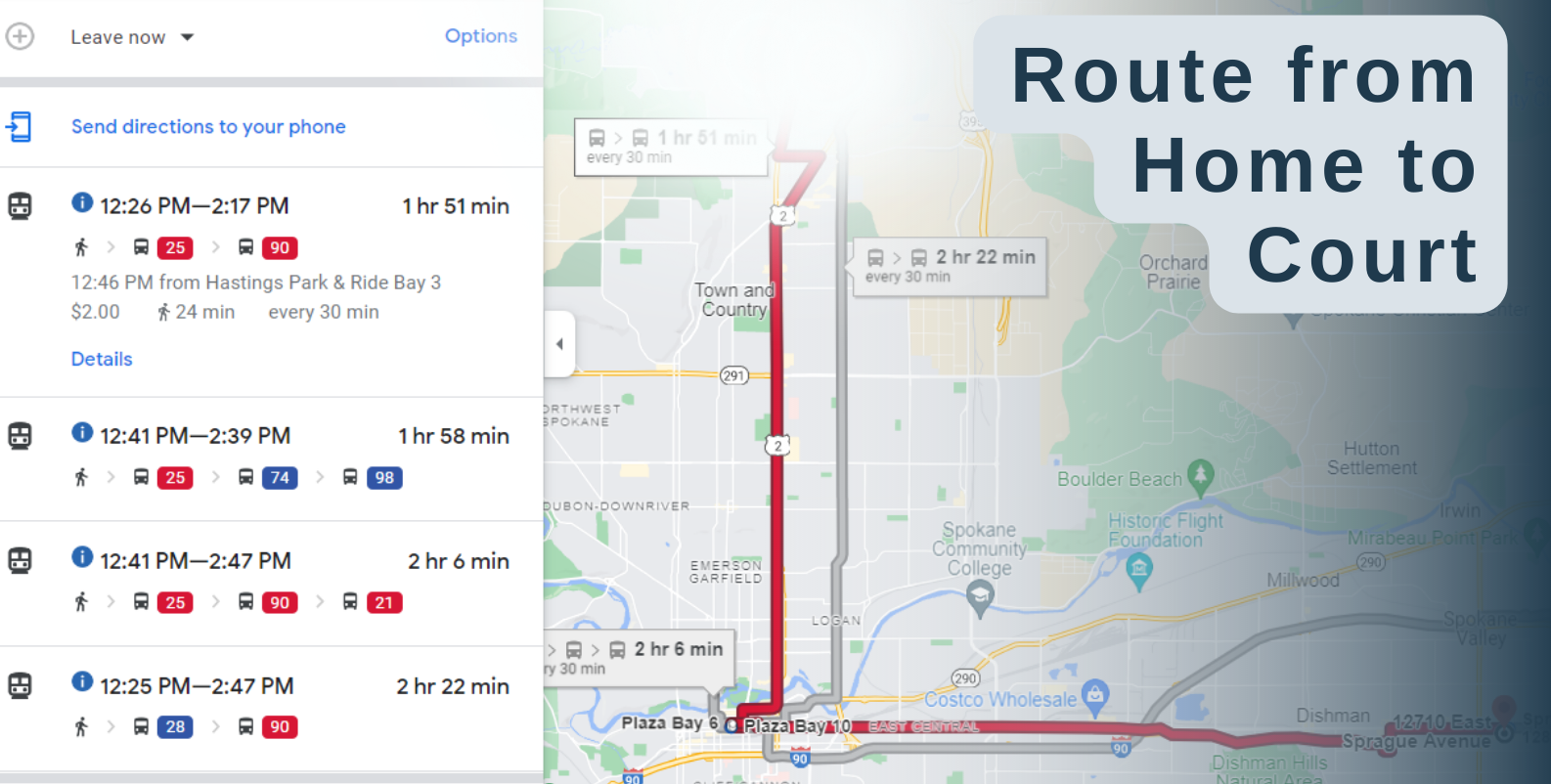

We have multiple courthouses in Spokane County, and on Mondays, I cover our Valley Courthouse, which is a 25-minute drive from my house. My judicial assistant said, “Hey, I take the bus all the time, just plug the address into the maps app, and it will show you the bus route.”

So, on Sunday night, I was trying to figure out how to get to the office without driving. I plugged in the address, and the map said, “There are no routes.” After trying to get a route to work for a while, I started to get frustrated, and my wife could hear me. Eventually, she got tired of my muttering and complaining and agreed to drive me to the office but told me I had to find my own route home.

In my reflection, I realize this is probably something people participating in my court programs face. We often tell participating individuals to ask family and friends for rides, but there is a cost associated with those favors. My wife clarified that this was my deal and that she didn’t have time to give me rides everywhere.

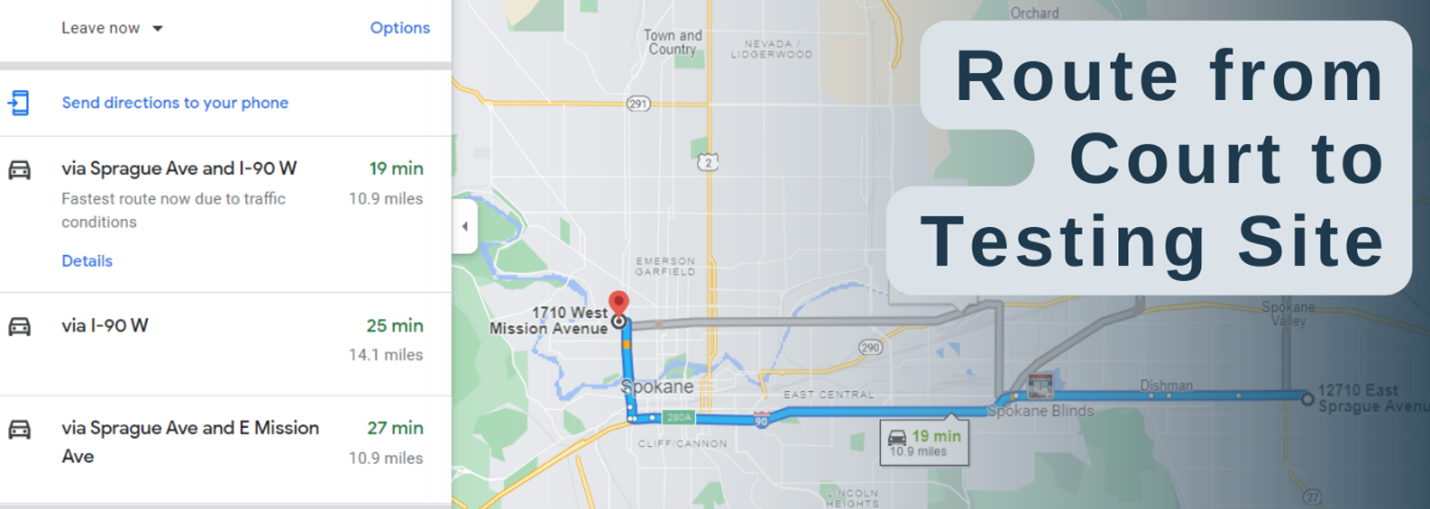

On Monday morning, my wife dropped me off at the Valley Courthouse. Once there, I called the UA center, and sure enough, I had to go in and test. I made a plan to take the test during my lunch break. Unfortunately, there was no way for me to take the bus and be able to get back to the court in time to start my afternoon docket. So, I ended up ordering a ride using a rideshare app. The round trip cost me $66, on top of paying for the UA test, which was $20.

As for the testing itself, I didn’t know what to expect. I knew it would be observed, but I didn’t realize the extent of an observed UA. First, they had me drop my pants to my ankles, and then they asked me to pull my shirt up and take a couple of steps back to where there were mirrors on the wall so they could see from all angles. All to make sure I wasn’t hiding a urine pouch. Finally, they handed me a cup and directed me to pee in it.

Even though I have a medical and sports background, and nakedness and urine samples don’t bother me in those contexts, this experience was very intimidating and uncomfortable.

Later in the day, I finally figured out how to get the bus home. And what would typically be about a 25-minute drive turned into a nearly 2-hour ordeal.

A pivotal memory of this first bus ride was the feeling of being out of place. I was in a suit carrying a briefcase, and I got a lot of whispering and pointing. I looked very different from everybody else on the bus. It was very uncomfortable.

It’s not very often that I am in a setting where I feel uncomfortable. And it was vital for me to feel that discomfort and what it is like to be “othered,” for lack of a better term. Eventually, we got to the park-and-ride stop, where I got off the bus and walked a mile and a half to my house in my suit, carrying a briefcase in 105-degree weather.

After that very long day, I had several observations. One was that having to use public transportation dramatically shrinks your day. Compared to the convenience of getting into the car and going, I spent a lot more time planning and organizing my route, not to mention the time I spent riding and walking. At one point in the week, I needed something from the store but realized I couldn’t drive and would have to walk. I made do without it.

The next day, I decided to ride my bike, which came with challenges. The route home is all uphill. It still took time and was physically inconvenient. I stuck to using the bus and walking for the remainder of the week.

I was pleased to wake up Saturday morning and know I could drive.

What did you learn from the experience that you have since used to adjust how you operate your mental health treatment court?

My mantra with people participating in my court was always, “Call early, test early.” But I learned that it isn’t always that simple. There were days I couldn’t call until I got to the courthouse. Then, with work, I couldn’t get to the testing site during lunch, so many logistics were involved, even when I called in the morning.

Another observation I had was the cost. Our court provides a bus pass to participants, but sometimes the bus doesn’t get you where you need to be or won’t get you there on time. Using a rideshare app is economically unrealistic for most participants.

Additionally, I think about how all I did was stop driving and submit to random UAs. I wasn’t having to worry about childcare or getting to my treatment appointments. Additionally, I didn’t have to contend with mental illness or financial constraints.

I have a better understanding of what it’s like to have to navigate public transportation and the humility involved with doing observed random UAs.

The response I get from my colleagues on the bench is, “This is an interesting thing you did, and I’m glad you did it, but it’s not for me.” So, they appreciate its value but can’t see themselves doing it.

My goal is to encourage other judges to step into the shoes of the people in their court. It’s one thing to hear somebody describe their experience. It’s a whole other thing to walk in those shoes.

Like what you’ve read? Sign up to receive the monthly GAINS eNews!