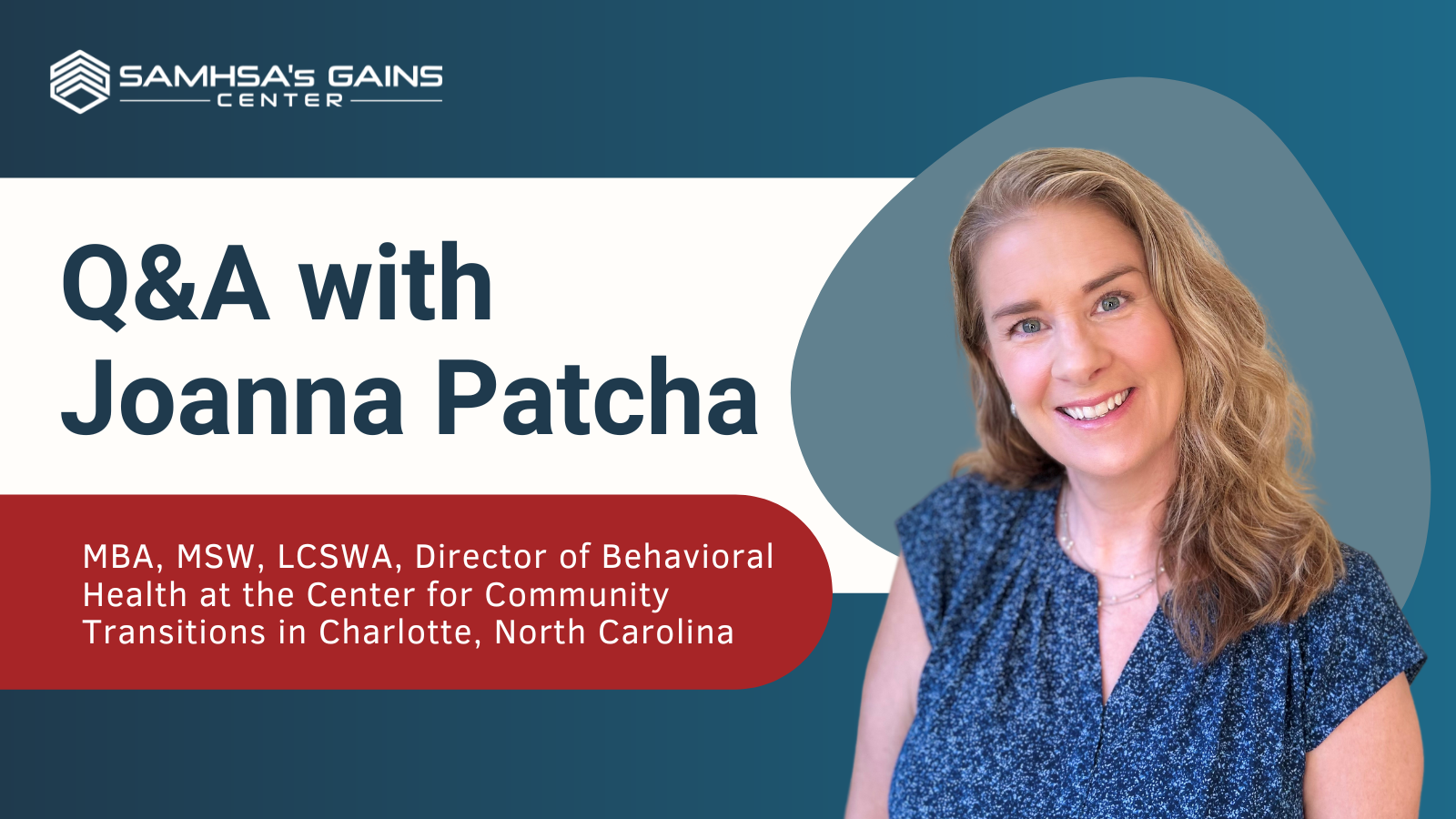

Your work helps formerly incarcerated individuals transition into society, providing therapy and support to these individuals and their families. Tell us about what called you to this work, including your journey from a corporate environment to the Center for Community Transitions (CCT).

I’ve always had a heart for social justice. I was privileged enough to work in the corporate world part time when I took a class through an organization called Just Faith. Through that experience, I found an inner calling. The course pushed me outside my comfort zone. We learned about the criminal justice system and the cycle of how people end up there. We had lunch with the women who reside at CCT, a 30-bed transitional facility in Charlotte, and I thought, “This is me. This is my neighbor, my mom, my grandmom.”

A few weeks later, I started volunteering at the CCT, which has three programs to support individuals and families affected by incarceration. One is a transitional detention facility where women serve the last 1-3 years of their sentence. The second is LifeWorks!, which offers reentry assistance, and the third is called Families Doing Time, which serves families dealing with the effects of having a loved one incarcerated because when an individual is incarcerated, the entire family system is affected.

CCT has its own behavioral health department, which you now lead. Why was a behavioral health department an organizational need, and what led to its creation?

There was a need and a desire for a behavioral health program prior to COVID-19, but no funding or staff. While the programs at CCT support individuals and families affected by incarceration, we didn’t have the financial or staff resources to meet the mental health and trauma needs of the individuals we serve.

Then during the pandemic, we identified the CCT transitional detention program as a perfect opportunity to engage individuals in treatment services. At the start of the pandemic, we had 30 women in the facility, but they were typically working 35-40 hours a week, so it didn’t feel crowded. But that all changed when COVID made it so these women couldn’t go to work or have family visits. The shared space suddenly felt smaller, and they were now further distanced from natural sources of social support. So, we brought in a therapist to help. We had some difficult conversations in the group, but we bonded through them and through the time we spent together.

Then in November 2020, via an anonymous donation, we established the Behavioral Health Department. The CCT Behavioral Health Department provides personalized support depending on the needs and concerns of the individual in the program. Our person-centered approach to treatment is founded on compassion and seeks to offer mental and emotional healing. Services are offered throughout the individual’s stay and focus on preparing her for a healthy and successful transition.

In addition to working at CCT, you also volunteer with Changed Choices, a nonprofit organization that provides a range of support services to women who are incarcerated in local, state, and federal systems. What are some of the common challenges women face upon reentry, and what supports are most needed?

About 65-70 percent of women experiencing incarceration are mothers, and the way incarceration affects that bond is a huge struggle. A lot of them have lost custody of their children. It’s heartbreaking to see women who haven’t talked to their kids in 5 or 10 years. We help them reconnect with their children and the child’s caregiver, who is the gatekeeper to their child.

Housing is a big hurdle and directly related to a person’s occupational skills, because if you don’t have a living wage you can’t sustain a household budget. We help with skills and training, whether that means going back to school or trade school.

So, the major challenges relate to children, housing, skills, and education. Most of the women we work with do not have a high school diploma. I think as a society we could do a better job with helping them get a degree or at the very least provide financial education and guidance around a career path. There are a limited number of programs offered at detention facilities that provide these crucial elements.

One of the foundational tenets of your faith involves “walking with the excluded.” You helped plan a 30 Days Out: The Re-entry Simulation event to build compassion for people returning to the community after incarceration. What is the simulation program, and how has your faith influenced this and other work you do in the community?

A reentry simulation gives participants an idea of the lived experience of transitioning back into a community after incarceration. I’d read about a reentry simulation put on by the Re-entry Partners of Mecklenburg County, and I wanted to bring it to my church community in Charlotte, North Carolina. Several members of the St. Peter Catholic Church, including myself, planned and hosted a simulation. At our first event there were 15 stations, and we had 20 volunteers and 50 participants. Each participant received a packet with basic information (their name, criminal background, life scenarios, etc.). They may have $100 or $10, and they had to figure out how to get housing, go to their therapist and parole officer, and get a bus pass. There are so many barriers right at the start.

We developed the simulation with the traditional criminal justice and governmental decision-makers in mind. What we found was that people who work in criminal justice spaces didn’t necessarily understand the adverse impacts of incarceration. We had participants coming through and saying, “I had no idea.” A police officer admitted that he was told to attend and didn’t want to come, but afterwards, he said it was “such an eye-opening event for me.” He wanted a class for his recruits. Because it was such a success, my church has decided to host a reentry simulation every other year.

As for my faith, I feel this is my calling from God. Whether it’s organized religion or not, we’re all here together in community, and our calling is to help one another through the journey.

Your work can certainly be emotionally challenging at times. What are three things you do to maintain your own mental and emotional well-being?

I work 3 long days, 30 hours a week. But I would rather work the 3 long days and have those days in between to refresh and regroup; it fills my spirit back up.

I listen to my body. That’s something I’ve learned through my social work practices, to listen to my body and hear what I need. And if my body says I’m exhausted, I rest. I want to bring my best to these women. I love my job and feel like it is such a blessing to be there with them.

Lastly, I’m a big pet lover. When I’m sitting on the couch doing work, I have two cats behind me, and the dog is at my feet.

Like what you’ve read? Sign up to receive the monthly GAINS eNews!