By Jennifer K. Johnson, JD, Principal, J.K. Johnson Advisors, LLC.

“To be a good lawyer, one has to be a healthy lawyer. Sadly, our profession is falling short when it comes to well-being.” National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, 2017[1]

According to the National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, the legal profession is at a crossroads: either prioritize the health and well-being the workforce, or risk losing the public trust. In its 2017 report on the state of the field, The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations For Positive Change, the task force highlights two recent studies that show high rates of chronic stress, substance use, and depression among both practicing lawyers and law students.[2] The report paints the picture of a profession in crisis.

These findings are incompatible with a sustainable legal profession, and they raise troubling implications for many lawyers’ basic competence. This research suggests that the current state of lawyers’ health cannot support a profession dedicated to client service and dependent on the public trust.[3]

For those lawyers working at the intersection of criminal justice and behavioral health, this call to action may be even more urgent. Unlike a traditional criminal docket where a criminal defendant has a fairly predictable and time-limited path to resolution of the charges, participants in collaborative courts make frequent and regular court appearances and sometimes spend years on a winding journey to stability and sobriety. Individualized treatment takes center stage and, as long as the person is in treatment, the criminal charges are no longer the focal point of the court proceedings.

Because of the emphasis on client well-being, lawyers assigned to problem-solving courts—both prosecution and defense—forge deeper and more personal professional relationships with the court participants than they might in another context. In fact, the entire courtroom is witness to the struggle of a population of people that has been left out of community-based behavioral health treatment, only to end up behind bars. These people often have multiple layers of trauma, most are addicted to substances, many suffer from serious mental illnesses, and a large number have serious medical issues. It is all too common for specialty court lawyers to see clients relapse, overdose, die by suicide, or fall victim to violence on the streets.

Listening day after day to stories of human suffering and violence takes a toll on the mental health of lawyers in the courtroom and puts them at risk of suffering from what is known as compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is the cumulative physical, emotional, and psychological effect of exposure to traumatic stories experienced when working in a helping capacity. According to Dr. Charles Figley, who coined the term in the mid-1990s,

We have not been directly exposed to the trauma scene, but we hear the story told with such intensity, or we hear similar stories so often, or we have the gift and curse of extreme empathy, and we suffer. We feel the feelings of our client. We experience their fears. We dream their dreams. Eventually, we lose a certain spark of optimism, humor and hope. We aren’t sick, but we aren’t ourselves. [4]

Compassion fatigue, sometimes called secondary or vicarious trauma, should not be confused with burnout, although the two conditions often occur together.[5] Burnout refers to a gap between expectations and outcomes where perceived demands are greater than perceived resources.[6] Burnout is caused by a number of factors, including long hours, lack of support, high levels of scrutiny, organizational failures, chronic tedium, and a lack of resources. Compassion fatigue, on the other hand, is connected to specific client issues. It tends to develop more slowly than burnout, and is directly related to the content of the material to which lawyers are exposed.[7]

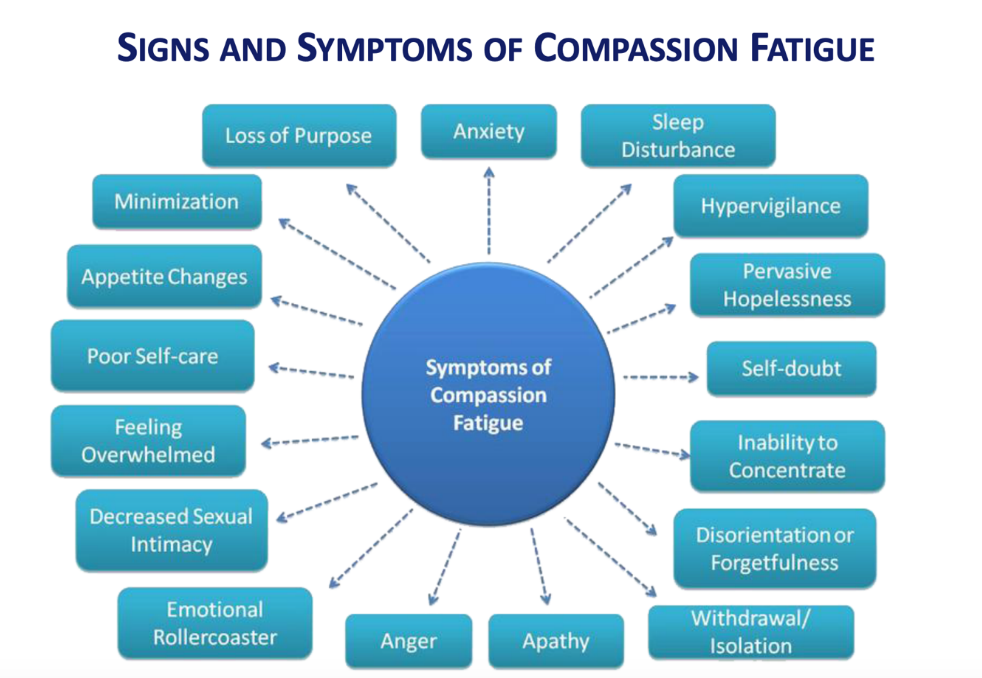

As science establishes a better understanding of the neurobiology of trauma, we have learned that symptoms of compassion fatigue are not just emotional, but physical and cognitive as well.[8] Emotional symptoms of compassion fatigue include chronic anxiety, self-doubt, withdrawal and isolation, irritability and anger, powerlessness, numbness, and intrusive concern about cases and clients. Physical symptoms include changes in breathing, changes in heart rate, difficulty sleeping, headaches, problems of the immune system and changes in appetite. Finally, cognitive symptoms include rigid thinking, difficulty concentrating, confusion and memory loss, inability to recognize cause and effect, loss of sense of direction, and minimization of problems.[9]

When Dr. Figley says, “We aren’t sick, but we aren’t ourselves,” he touches on an important point about the subtlety of what attorneys may experience. Lawyers may not recognize and appreciate emotional, physical, or cognitive distress as the expression of secondary trauma. In fact, they may not realize anything is wrong at all.

What lawyers too often do is excuse, minimize, or ignore the symptoms and simply tough it out: I always have trouble sleeping, I’m used to the stress, I can handle it, I don’t have time to go to the doctor, I just need to suck it up. They may also find other maladaptive coping strategies to deal with the chronic stress. As a group, lawyers have dramatically high rates of alcohol and drug use, suicide, impaired relationships, mental health problems, and medical problems.[10]

Over time, these dysfunctional ways of processing stress have combined with a professional culture that perpetuates the dysfunction to create a population of impaired attorneys and a profession at risk of losing credibility. The status quo is not sustainable.

The good news is, we can do better.

The task force report sets forth five straightforward recommendations for employers that are intended to minimize lawyer dysfunction and reinforce the positive relationship between wellness and excellence in the practice of law: [11]

- Identifying stakeholders and the role that each of us can play in reducing the level of toxicity in the profession

- Ending the stigma surrounding help-seeking behaviors

- Emphasizing that well-being is an indispensable part of a lawyer’s duty of competence

- Expanding educational outreach and programming on well-being issues

- Changing the tone of the profession one small step at a time

The American Bar Association (ABA) followed up on the work of the task force by establishing the Working Group to Advance Well-Being in the Legal Profession. To date, more than one hundred law firms, corporations, and law schools have signed on to the ABA’s Well-Being Pledge, which calls on legal employers to acknowledge the crisis and commit to making lawyer wellness a priority.[12] Ideally, these efforts will become the norm and reach all areas of law practice.

In addition to practicing attorneys, law students have also begun to prioritize their own health. Stanford professor Ronald Tyler authored a law review in 2016 entitled, The First Thing We Do, Let’s Heal All the Law Students: Incorporating Self-Care into a Criminal Defense Clinic. According to Professor Tyler, Stanford has created an innovative self-care curriculum in the Stanford Criminal Defense Clinic that encourages mindful self-reflection, teaches coping skills, and increases resilience.[13] At Berkeley Law, first- and second-year students launched the Peer Wellness Coalition in 2018. The student-run group has plans to begin the conversation about wellness during first-year orientation and weave that dialogue throughout the three-year curriculum.

When we understand the risk factors that make us vulnerable and the resiliency factors that make us strong, we are better prepared for the work that we do. As individuals and as a profession, we can and should take measures to avoid, mitigate, and reduce compassion fatigue. Awareness is a brilliant first step.

For more information and supports, check out the following resources:

- The “Trauma Training for Criminal Justice Professionals” provides information for improving services to individuals who have experienced trauma and are involved in the justice system. To find a certified trainer near you, visit this webpage: https://www.samhsa.gov/gains-center/trauma-training-criminal-justice-professionals

- See the GAINS Center’s video newsletter article by Dr. Lisa Callahan on “Recognizing Compassion Fatigue, Vicarious Trauma, and Burnout in the Workplace,” from January 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aS7Rk5RFF20&feature=youtu.be.

[1] National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being, The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations For Positive Change, (Author, 2017), p. 1. (Hereafter “Path to Lawyer Well-Being”). The Task Force was conceptualized and initiated by the American Bar Association Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs (CoLAP), the National Organization of Bar Counsel (NOBC), and the Association of Professional Responsibility Lawyers (APRL).

[2] Patrick R. Krill, Ryan Johnson, and Linda Albert, “The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Attorneys,” Journal of Addiction Medicine 10, no. 1 (2016): 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000182.

[3] Path to Lawyer Well-Being, 1.

[4] See generally, Charles R. Figley, ed. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized 1, (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1995), 1-20.

[7] Norton, 988

[8] Norton, 989

[9] Norton, 989

[10] Krill, Johnson, and Albert, “The Prevalence of Substance Use,” 46–52; see generally Dylan Jackson, “Lawyers, Judges at High Risk for Mental Health Issues,” Daily Business Review, March 1, 2019, https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/2019/03/01/lawyers-judges-at-high-risk-for-mental-health-issues/

[11] Path to Lawyer Well-Being, 10-11.

[12] “Working Group to Advance Well-Being in the Legal Profession,” American Bar Association, last modified April 12, 2019, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/lawyer_assistance/working-group_to_advance_well-being_in_legal_profession/.

[13] Ronald Tyler, “The First Thing We Do, Let’s Heal All the Law Students: Incorporating Self-Care into a Criminal Defense Clinic,” Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law 21, no. 2 (2016): 1.