Soros Justice Fellow, Open Society Foundation

1. You have recounted that as a young person prior to becoming incarcerated, you had experienced war, family displacement, social isolation, and bullying at school. Recognizing that many people who experience incarceration have histories of trauma, what do you recommend can be done to better support communities where there is a high incidence of trauma to minimize risk factors for criminal justice involvement for the people who live there?

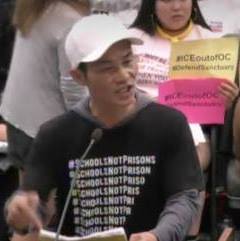

Based on my experiences, there is a sense of discrimination that exists in all communities, regardless of race, when it comes to issues related to incarceration and or justice system. I find it helpful to pay close attention to the school-to-prison pipeline, and encourage schools and parents to work together to identify issues the young person may be experiencing and address them before they get out of hand. Isolation, loneliness, and bullying can occur, which might lead the young person down the wrong paths.

Aside from the family and school working together to identify problems, the community, too, must play an active role in supporting both the family and the school through available mental health resources. This allows conversations that help identify the problem and prevents involvement with law enforcement, which is the last option. In my experiences, the less law enforcement involvement, the better. Once the police are called, regardless of fault, there is no possibility for reconciliation, rather a high risk of incarceration, for those who endure what I endured.

2. You founded the organization, Asian & Pacific Islanders Re-entry of Orange County (California). In your experience,

a. What are commonly experienced challenges among the people you have worked with who identify as Asian or Pacific Islander and are returning to the community after incarceration?

There is a high degree of discrimination within Asian-Pacific Islander (API) communities against those who return after incarceration, making it very hard for people to get support to rebuild their life. This often results in disappointment and frustrations in maintaining a life free of justice involvement. The API communities in Orange County, California are very reluctant to get involved with justice-involved people for fear of shame. Discrimination and shame are two challenging factors that can force a formerly incarcerated person to return to a life of crime or substance use as a way to cope and survive.

b. Can you share an example of how your organization tailors programming to support this specific population?

Asians & Pacific Islanders Re Entry of Orange County (APIROC) has been a community group since it was established—it is non-funded and does not have 501(c)(3) status. Most of the expenses are paid out of pocket or through private donations to help a person recently released from prison. Our vision is to provide basic reentry supports to a person recently released from prison, jail, or detention; to work with families of people who are incarcerated and guide them on how to support their loved ones; and to work with survivors and perpetrators of crimes and perpetrators to create a restorative dialogue, so that both can understand and reconcile with one another. We hope to create healing circles so those involved can share and heal, rather than to live alone with pain because of discrimination and shame, which dominate the community.

3. During the years you were in prison, you became a peer health educator and a reentry program specialist. Was there any specific person or program that was particularly helpful to you in becoming the person you are today?

All of the programs I participated in played a key role in how I am able to assist and support the community today, from Peer Health Educator, where I helped people understand safer practices of drug use and sexual activity, to Reentry Specialist, where I helped people prepare short-term and long-term parole plans in order to deal with obstacles they might encounter once released. Most importantly, I found that participating in the Victim and Offender Education Group hosted by the Insight Prison Project had a powerful impact on how to identify your wrongs and work towards preventing future harm to yourself and others. Hearing about the suffering and pain experienced by victims, the questions of “why” asked by victims, and finding commonalities among those who talked about suffering helped me to gain the courage to look into my behavior, trace the root cause of my self-destruction, and work to prevent myself from recommitting these offenses, while also helping others to not walk the same path.

4. What would you like to see mental health or criminal justice professionals doing better to serve Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with histories of trauma who have become justice-involved?

For the past 8 years, I have worked to establish a support system for justice-involved APIs. I continue to see a lack of understanding from mental health and criminal justice professions when it comes to dealing with API populations that have experienced incarceration. On a broader level, there is not much understanding about the history, culture, and traumas that formerly incarcerated APIs and their families have experienced. Furthermore, there are not many therapeutic treatments or programs that are free or low-cost to help those impacted deal with their trauma as they work to rebuild their life after being released from prison.

There is often a language barrier, which makes receiving services incredibly difficult. Most APIs who return from prison are not fluent in English; therefore they do not receive needed assistance, or they are turned away from help because of their inability to communicate in English. Additionally, the API volunteers who are working to support the reentry needs of this population are usually from younger generations and are not very fluent in native languages: Vietnamese, Cambodian, Chinese, etc. I have witnessed APIs who were formerly incarcerated turn away help out of shame related to language barriers.