Up to 63 percent of individuals in jail custody have substance use disorder (SUD), and 37 percent used drugs at the time of offense. Prolonged or heavy use of substances can be fatal: in-jail deaths from drug or alcohol intoxication quadrupled between 2000 and 2019. More than half of overdose deaths among individuals who were formerly incarcerated involved polysubstance use (i.e., use of more than one substance).

Of the many physical, psychological, social, and legal risks faced by people with SUD, perhaps least recognized is the danger of withdrawal. Individuals frequently experience withdrawal at the time of entry into jail, when access to their substance of choice is abruptly cut off. Within the first few hours and days of detainment, people who have suddenly stopped using substances may experience withdrawal symptoms, which can be managed if recognized and treated. Failing to help an individual manage their withdrawal symptoms can lead to serious health complications and death:

- Potential health complications include anxiety, depression, seizures, vomiting, dehydration, hypernatremia (elevated blood sodium level), heart problems, hallucinations, and tremors.

- A study of deaths in U.S. jails revealed that alcohol was involved in 76 percent of withdrawal-related deaths, confirming longstanding research findings of the lethality of alcohol withdrawal. Opioids were the drug most often involved in the other withdrawal deaths studied.

- The risk for suicidal ideation and attempts is higher among individuals with SUD than those who do not have SUD, and stimulant withdrawal is associated with suicidal ideas or attempts. Suicide is the leading single cause of death in jails.

While most jails (but not all) report having a withdrawal protocol in place, the protocols may not be evidence-based or sufficient to meet treatment standards. Suffering and death from withdrawal in jails are preventable, reinforcing the need for withdrawal management policy and protocols that are aligned with legal, regulatory, and clinical standards. Moreover, jails are legally obligated to provide adequate health care for those they hold in confinement, including care of individuals experiencing withdrawal (see figure 1). Without adequate care, jail administrators may fall short of meeting this duty and treatment standards. Jails, corrections staff, government agencies, public officials, medical staff, and third-party service providers may be exposed to liability. Large financial settlements or judgements, attorney’s fees, and court-enforced remediations increase costs to local governments and jails.

The Guidelines

For more information on the legal obligation of jails to provide adequate health care, go to:

- Managing Substance Withdrawal in Jails: A Legal Brief

- The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Opioid Crisis: Combating Discrimination Against People in Treatment or Recovery

Figure 1

In response to the urgent need for withdrawal management policy and protocols, the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) supported the development and release of Guidelines for Managing Substance Withdrawal in Jails: A Tool for Local Government Officials, Jail Administrators, Correctional Officers, and Health Care Professionals (Guidelines). It is designed to help jails (including detention, holding, and lockup facilities) and communities in providing effective health care for adults (18 years of age and older) who are at risk for or experiencing substance withdrawal and are sentenced or awaiting sentencing to jail, awaiting court action on a current charge, or are being held in custody for other reasons (e.g., violation of terms of probation or parole).

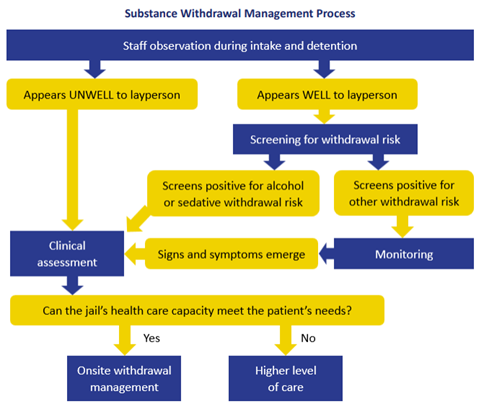

The Guidelines present clinical recommendations and supporting narrative on standards of care for managing withdrawal from alcohol, sedatives, and stimulants, as well as for avoiding or minimizing opioid withdrawal through effective opioid use treatment. The recommendations are contextualized within a universal process for managing substance withdrawal (figure 2), which includes the following:

- Regular and active observation for signs and symptoms of intoxication and withdrawal (and other indicators of being unwell), beginning at the individual’s arrival to the facility. The importance of staff training on recognizing signs and symptoms cannot be overstated, particularly considering the likelihood of polysubstance use among individuals entering custody.

- Screening for risk of withdrawal among all individuals, regardless of their length of stay in jail.

- Referral, based on observation and screening results, for either immediate clinical assessment or monitoring for the emergence of withdrawal indicators.

- Clinical assessment to inform whether the patient’s needs can be addressed at the jail or require transfer to a higher level of care.

Figure 2: The substance withdrawal management process, taken from the Readiness for Implementation Toolkit

However, the extent to which the needs of patients can be met within the jail is highly dependent on its size, staffing, and capacity. For example, does the jail have adequate staffing to immediately screen all individuals entering the jail for current intoxication, current withdrawal, or risk of withdrawal?

Linda J. Frazier, MA, RN, MCHES, a key contributor to the development of the Guidelines, comments, “From my years of working as a corrections manager in a rural state, I observed firsthand how difficult it is for small-town jails to provide 24/7 health care due to workforce issues and limited resources. For example, they may lack the internal capacity or community resources to offer the full range of withdrawal pharmacology. The Guidelines are sensitive to the constraints of under-resourced jails and offer alternatives, such as using well-trained custody staff to conduct screening.”

Appreciating that each jail will start at a different place due to its unique circumstances, BJA and NIC developed a Readiness for Implementation Toolkit to help jail administrators, in collaboration with correctional staff, healthcare professionals, and community partners, build on their current efforts to manage substance withdrawal. The toolkit includes an implementation readiness assessment; checklists for jail administrators, health care professionals, and local government officials; and an assessment of correctional officers’ training needs.

To request training and technical assistance on implementing the Guidelines or to access other relevant resources, such as an e-learning module for jail staff on the basics of screening for SUD, visit the online Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Use Program Resource Center.

Guidelines for Managing Substance Withdrawal in Jails: A Tool for Local Government Officials, Jail Administrators, Correctional Officers, and Health Care Professionals was supported by Grant No. 2019-AR-BX-K061, awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. Points of view or opinions in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Like what you’ve read? Sign up to receive the monthly GAINS eNews!